Posture and Pain

Clients, patients, and athletes may develop static and dynamic postural deviations for many different reasons. Postural deviations may be due to repetitive movements associated with the client or patient’s occupation, hobbies, or sport. These deviations could also be due to prolonged periods of static postures, such as standing or sitting. These repetitive movements and/or prolonged static postures can lead to muscular imbalances, and in turn, may lead to tissue trauma, inflammation, and pain over time.

This Muscle & Motion article will explore a common static postural deviation termed upper crossed syndrome.[1]

We will also cover the muscular imbalances associated with upper crossed syndrome. As well as an effective strength training exercise to assist with correcting these muscular imbalances and static postural deviation in an attempt to decrease risk of injury and improve performance.

Upper Crossed Syndrome

It is crucial to note that not all cases of upper crossed syndrome result in pain. The causes of back and neck pain are multifaceted and cannot be attributed solely to a single factor. Instead, they involve a complex interaction of biological, psychological, and social factors that vary from person to person. These factors are not mutually exclusive and can influence one another. Let’s dive into the mechanical theory behind upper crossed syndrome:

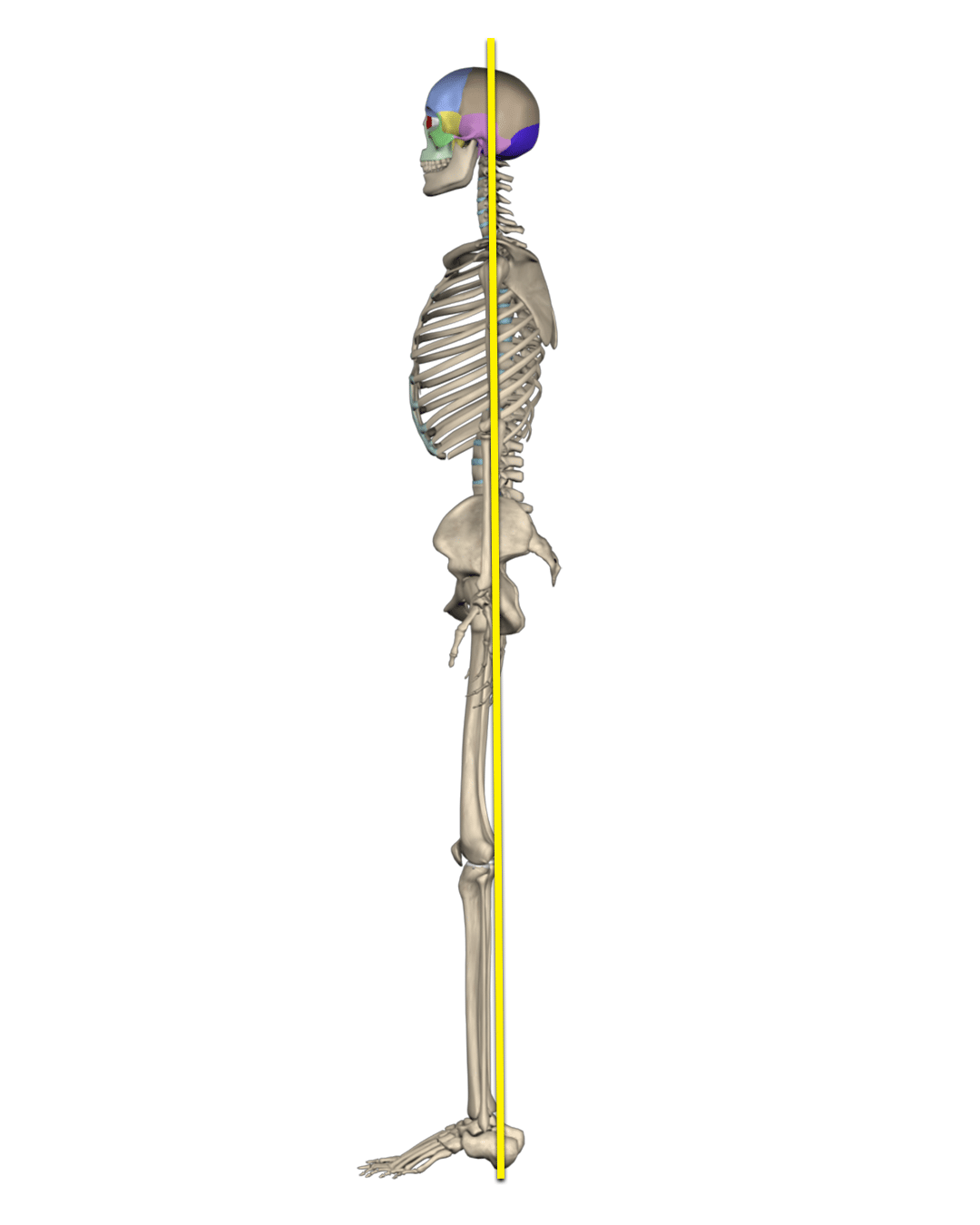

When assessing static posture from a lateral view, the ideal posture of the thoracic spine, shoulder girdle, shoulder joint, and head and neck are to be in a neutral position. This neutral position is characterized by: a normal kyphotic curve of the thoracic spine, neutrally positioned scapulae (i.e., not protracted and/or anteriorly tilted), shoulder joint in line with the hip, knee, and ankle joints and not internally rotated, and the ear in line with the shoulders.[2]

Individuals with upper crossed syndrome commonly exhibit an excessive kyphotic curve, protracted and/or anteriorly tilted scapulae (i.e., rounded shoulders), possibly internally rotated shoulders (i.e., elbows pointed laterally and palms facing posteriorly), and a forward head where there is excessive cervical flexion and capital/cranial extension with the head jutting forward and the ear falling in front of the shoulder joint.[1]

Please note that some clients may not exhibit all of these postural deviations of upper crossed syndrome together. For example, a client may exhibit an ideal kyphotic curve and scapulae and shoulder joint posture, but exhibit forward head posture.

With upper crossed syndrome, the pectoralis major and minor, the latissimus dorsi, teres major, and subscapularis are commonly in a shortened position, along with the suboccipital muscles, upper trapezius, and levator scapulae. Whereas the deep cervical flexors that draw the chin in towards the spine, as well as the rhomboids and middle fibers of the trapezius, are commonly in a lengthened position.[1] Thus, this static posture deviation being termed by Vladimir Janda as “upper crossed syndrome”.[1]

Upper crossed syndrome has been associated with rotator cuff pathologies, biceps tendonitis, and shoulder joint instability.[1] Whereas forward head posture may lead to mid- to upper-back pain, neck pain, thoracic outlet syndrome, temporomandibular disorders, and tension headaches.[1]

Effects of Upper Crossed Syndrome on the Musculoskeletal System

With upper crossed syndrome the protractors of the scapulothoracic articulation/scapulae (i.e., specifically the pectoralis minor) and the internal rotators of the shoulder joint (i.e., pectoralis major, latissimus dorsi, teres major, and subscapularis) are commonly in a shortened position, it may be advisable to try to address this with utilizing modalities to assist in increasing muscle flexibility and joint range of motion, such as self-myofascial rolling, static stretching, and dynamic stretching.

Conversely, on the back side of the body, the retractors of the scapulothoracic articulation/scapulae (i.e., rhomboids and middle fibers of the trapezius), as well as the external rotators of the shoulder joint (i.e., infraspinatus, teres minor, and fibers of the posterior deltoid) are commonly lengthened and should be addressed through strengthening exercises. Due to the synergistic relationship between the scapulothoracic articulation of the scapulae on the ribcage and the shoulder joints, scapular protraction naturally accompanies shoulder external rotation, specifically during greater degrees of external rotation.[3]

Because individuals with upper crossed syndrome exhibit rounded shoulders, exercises that focus on strengthening the scapular retractors and shoulder external rotators could be beneficial to include in these individuals’ exercise programs. Retraction can be accomplished with isolated scapular retraction exercises or any multi-joint horizontal pulling/rowing exercises (e.g., seated rows, inverted rows, and reverse flys).

Whereas shoulder external rotation can be accomplished through a variety of strength training exercises within various planes of motion utilizing multiple modalities, such as bands, dumbbells, weighted balls, and even suspension trainers.

Shoulder External Rotation (Mini Band) with Scapular Retraction

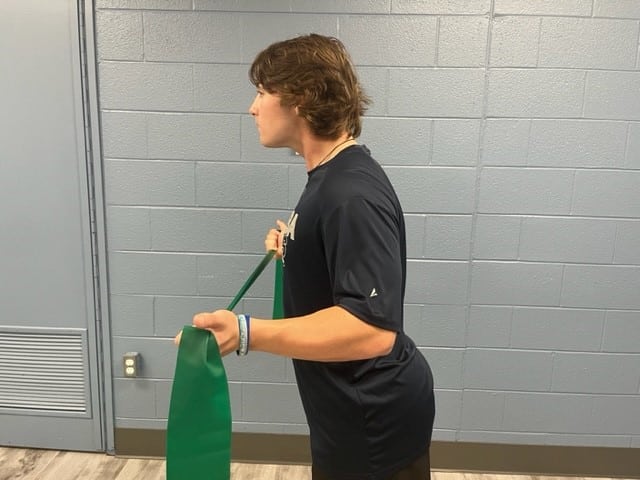

Many shoulder external rotation exercises are commonly performed unilaterally. However, if a fitness professional is looking for an exercise that strengthens both shoulders’ external rotators, as well as the scapular retractors simultaneously, the bilateral shoulder external rotation with scapular retraction exercise with a band can be the perfect exercise.

Step by step on how to do this exercise:

- To perform this strength training exercise, the client will stand with the feet shoulders’ width apart

- The client should tuck the chin in towards the spine (not down towards their chest) to where the ears are in line with their shoulders.

- The client should then draw the belly button in towards the spine while bracing the abdominals to restrict any compensatory movement at the lumbar spine (e.g., excessive lumbar extension or lordosis) while performing the exercise due to relative flexibility.

- The client will stabilize the scapulae by bringing them back and down (i.e., slight retraction with depression).

- Then the client will grab the band with both hands and firmly tuck their elbows into their sides as if they were holding a playing card between their upper arm and their torso.

- The client will externally rotate both shoulders, while simultaneously retracting their scapulae when approaching the end range of motion of shoulder external rotation.

- The client can use a one- to two-second concentric contraction (i.e., external rotation and retraction), a two-second isometric contraction while in external rotation and retraction, and a two-second eccentric contraction returning to the start position.

- Due to the scapular retractors and shoulder external rotators being primarily responsible for muscular endurance and stabilization, as opposed to strength or power, it is recommended that 1-2 sets of 12-15 repetitions be performed.

- Please note that this exercise can serve as a great movement preparation exercise prior to common upper-body resistance training exercises (e.g., chest press, shoulder press, lat pulldowns, and seated rows).

Common Movement Compensations

One common compensation seen while performing this exercise is the client performing excessive retraction to compensate for a lack of or weakness of shoulder external rotation. Although the client does want to retract the scapulae during initial shoulder external rotation, it should be a natural synergistic movement towards the end of shoulder external rotation range of motion. Therefore, shoulder external rotation should not be compromised in leu of excessive or exaggerated protraction and retraction of the scapula.

Another common compensation, possibly due to a lack of shoulder external rotation range of motion and/or strength, is the client performing shoulder abduction while attempting to externally rotate their shoulders.

The fitness professional will know if the client is abducting their shoulder joints if their elbows come away from the sides of their torso while performing external rotation and the imaginary playing card would fall to the floor. A good way to control for this compensation may be placing something like a folded towel under each arm between the client’s upper arm and torso. If the towel falls to the floor, the client is most likely abducting their shoulder joint too much.

If the client lacks the final degrees of scapular retraction during maximal shoulder external rotation, the client may exhibit excessive extension/lordosis in the lumbar spine due to relative flexibility.

Another compensation seen in the spine during this exercise may be a jutting movement of the head forward into cervical flexion with capital/cranial extension during the final degrees of shoulder external rotation and scapular retraction.

Again, the client may exhibit this movement compensation due to a lack of scapular retraction toward the final degrees of the movement.

A Great Exercise for Pretty Much Everyone

Although this is just one of many exercises to assist in addressing upper crossed syndrome, it is a great exercise. This exercise can be extremely useful for individuals who sit for extended periods of time, as well as overhead athletes (e.g., baseball, softball, and volleyball) whose sports require forceful shoulder internal rotation with scapular protraction and anterior tilting.

At Muscle and Motion, we believe that good posture is essential for your long-term health and well-being. Our Posture App can help you improve your posture and reduce pain. Sign up for free today!

References:

- Page, P., Frank, C., & Lardner, R. (2010). Assessment and treatment of muscle imbalance: The Janda approach (pp. 52-53). Human Kinetics.

- Conroy, V. M., Murray, B., Alexopulos, Q. T., & McCreary, J. B. (2024). Kendall’s muscles: Testing and function with posture and pain (6th ed.) (pp. 37). Wolters Kluwer

- Floyd, R. T. (2021). Manual of structural kinesiology (21st ed.) (pp. 120). McGraw Hill.