This Muscle and Motion detailed guide will provide you with everything you need to know about each type of joint.

Joints are the structures that connect every two bones in the skeletal system. Types of joints can be categorized based on the type of tissue present, such as fibrous, cartilaginous, or synovial , or by how much movement they allow, ranging from no movement (synarthrosis) to limited movement (amphiarthrosis) to unrestricted movement (diarthrosis).

Joint classification by tissue type:

Fibrous joints

Fibrous joints are held together by fibrous connective tissue, with no space between the bones. As such, most do not permit movement. There are three types of fibrous joints: sutures, gomphosis, and syndesmosis.

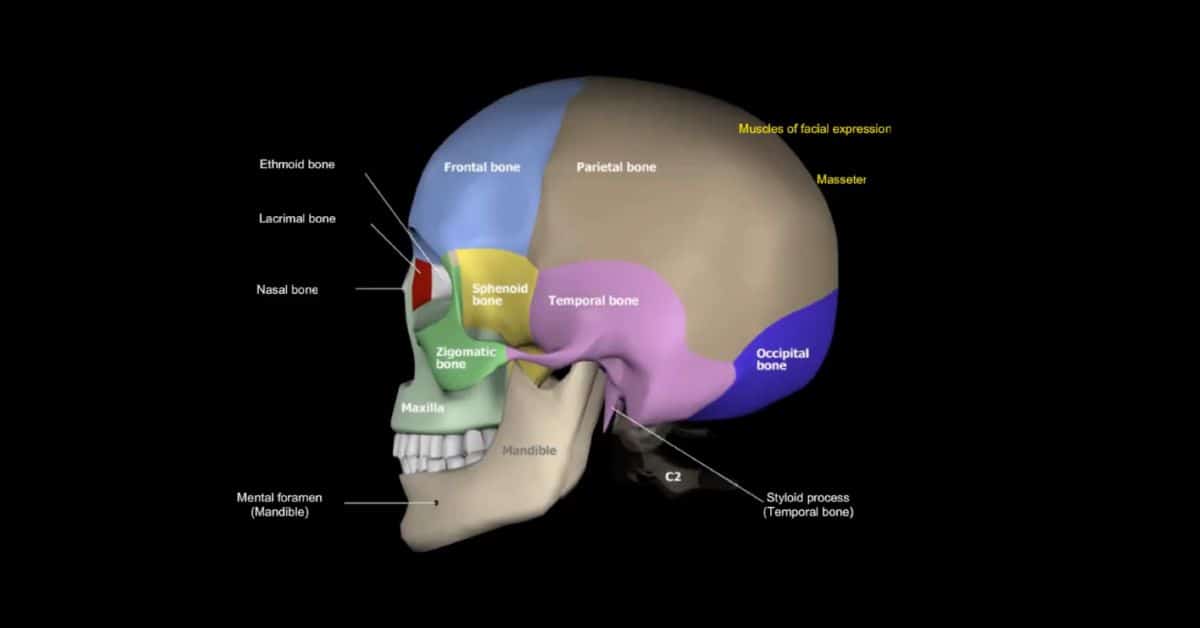

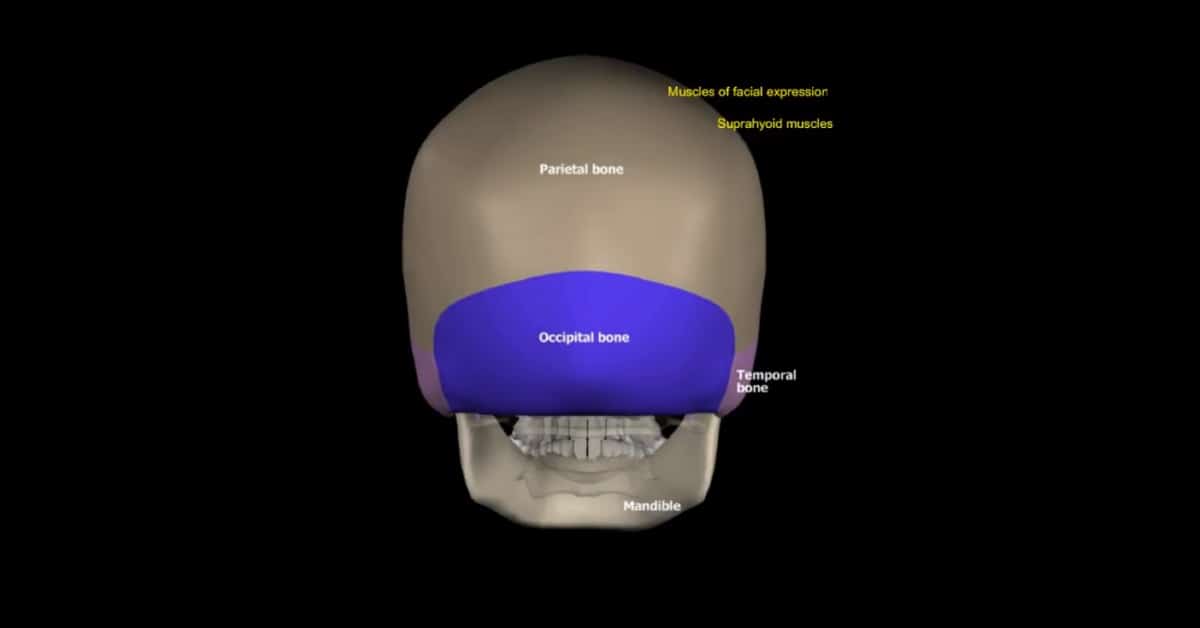

- Sutures are only found in the skull, where adjacent bones are held together by a thin layer of connective tissue called a sutural ligament.[1]

- Gomphosis joints form only between the teeth and the adjacent bone. These joints are held together by short collagen fibers in the periodontal ligament, which runs between the root of the tooth and the bony socket.[1]

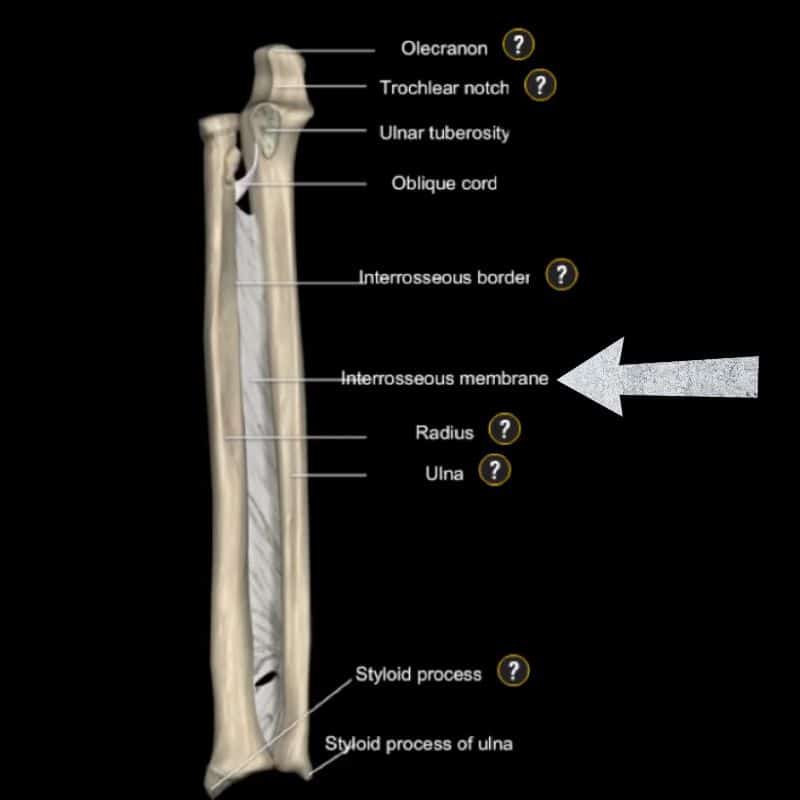

- Syndesmosis joints connect two adjacent bones using ligaments. Syndesmosis joints include the ligamentum flavum, which connects the neighboring laminae of the vertebrae, and the interosseous membrane, which links the radius and ulna together in the forearm.[1]

Cartilaginous joints

Cartilaginous joints are joints in which two bones are connected by cartilage. There are two types of cartilaginous joints: synchondroses and symphyses.

- Synchondrosis joints are typically found between children’s bones, where the bones are separated by a layer of cartilage. For example, the growth plate between the head and shaft of developing long bones enables bone growth and eventually fuses, becoming completely ossified.

- Symphysis joints are joints in which two separate bones are joined together by a layer of cartilage. These joints are usually found in the middle of the body, such as the pubic symphysis, which connects the two pelvic bones, and the intervertebral discs, which link adjacent vertebrae.[1]

Synovial joints

Synovial joints are the most common type of joint in the body. These joints enable a range of motions between two bones and are covered with a thin layer of cartilage that acts as a protective layer and helps to maintain the synovial fluid, which allows the joint to move smoothly. Synovial joints are characterized by a joint cavity filled with synovial fluid secreted by the synovial membrane (synovium).

The articulating surfaces of the bones are covered by hyaline cartilage, and the articular cartilage and the synovial membrane are continuous. Some synovial joints may have an articular disc or meniscus between the bones. This fluid-filled space is where the bones come into contact with each other.

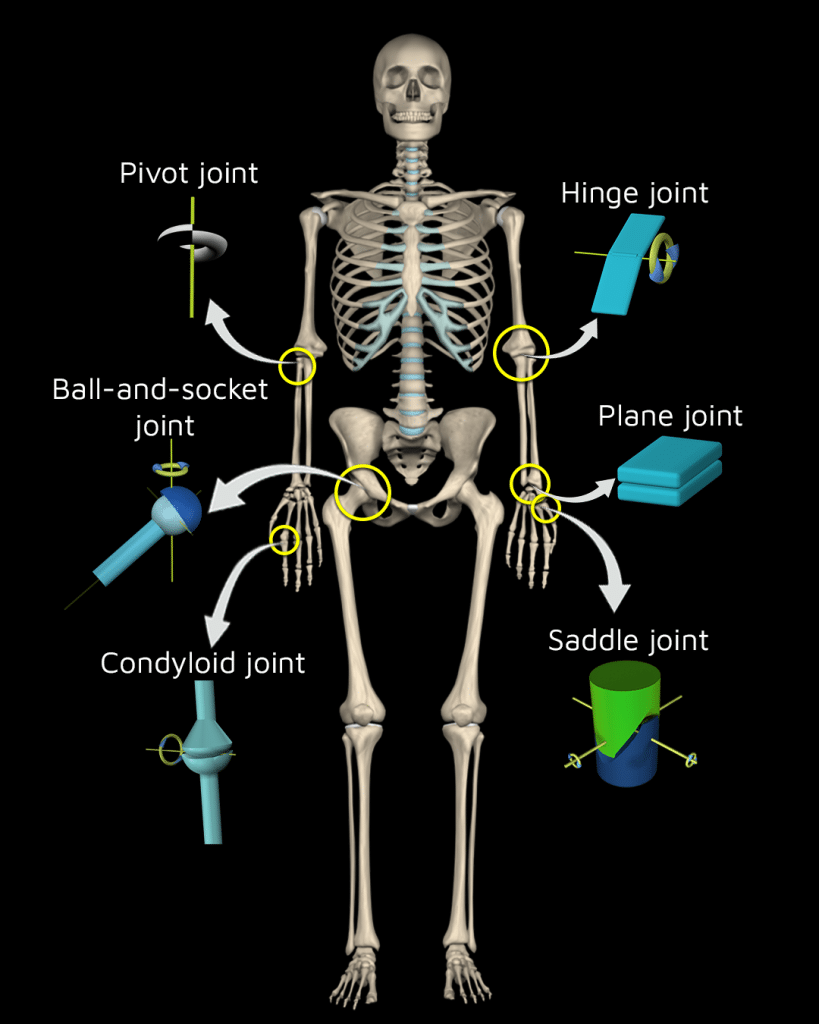

There are six types of synovial joints: plane, pivot, hinge, condyloid, saddle, and ball and socket joints.

Let’s start to review each of those joints in detail:

Plane joints

A plane joint (AKA arthrodial joint or gliding joint) is a joint type in which the articular surfaces are essentially flat and allow only short nonaxial gliding movements. Tight joint capsules usually limit these joints. Examples of this form of articulation are found in the following:

- Clavicle: acromioclavicular joint.

- Foot:: intertarsal and joint.

- Hand: intercarpal joint.

- Spine: zygapophyseal joint.

Pivot joints

A pivot joint (AKA trochoid joint, rotary joint, or lateral ginglymus joint) is a synovial joint whose movement axis is parallel to the long axis of the proximal bone. It is a uniaxial joint that typically has a convex articular surface. This joint allows movement around one axis that passes longitudinally along the shaft of the bone, permitting rotation. Examples of this form of articulation are found in the following:

- Proximal radioulnar joint

- Distal radioulnar joint

- Median atlantoaxial joint

Hinge joints

A hinge joint, also known as a ginglymus or ginglymoid joint, is a joint that allows motion only in one plane, usually flexion and extension. It may also include slight rotational or side-to-side movements, as is seen in the knee and ankle joints. Examples of this form of articulation are found in the following:

- Elbow joint (between the ulna, radius, and humerus).

- Knee joint.

- Ankle joint, also known as the talocrural joint.

- Interphalangeal joint.

Saddle joints

A saddle joint, named due to its resemblance to a saddle on a horse’s back, also known as a sellar joint, is a highly mobile joint found in only a few parts of the body. It is characterized by opposing articular surfaces with a reciprocal concave, convex shape. The movements of saddle joints are similar to those of the condyloid joint and include flexion, extension, adduction, abduction, and circumduction. However, the saddle joint does not allow axial rotation. Examples of this form of articulation are found in the following:

- Thumb: carpometacarpal joint.

- Thorax: sternoclavicular joint.

- Heel: calcaneocuboid joint.

Ball-and-socket joints

A ball and socket joint, also known as a spheroid joint, has a ball-shaped surface of one rounded bone that fits into a cup-like depression of another bone. The distal bone can move around in several axes with one common center, enabling the joint to move in many directions. Due to this highly mobile structure, it can perform many actions in different planes: flexion-extension, internal/external rotation, and adduction-abduction. Examples of this form of articulation are found in the following:

- Hip: the femur (ball) rests in the pelvis’s cup-like acetabulum (socket).

- Shoulder: the humerus (ball) rests in the cup-like glenoid fossa (socket).

Incorporating the Strength Training App into your fitness journey will take your workouts to the next level.

Download now from any device and sign up for free to try and experience the effectiveness of training smarter and better!

Reference

Drake, R. L., Vogl, A. W., & Mitchell, A. (Eds.). (2014). Gray’s Anatomy for Students (3rd ed.). Elsevier – Health Sciences Division.

Written by Uriah Turkel, Physical Therapist and Content Creator at Muscle and Motion.